The UK’s record of building nuclear plants is dismal. Yet, as Tim Probert explores, previous exercises may seem like a walk in the park compared to building a new fleet of reactors in a liberalized power market. This article was first published in the October 2012 issue of Energy World magazine.

Few would disagree that while the UK has often been a pioneer in nuclear power, its track record of building atomic power stations is, at best, mixed. From the troubled Magnox programme to the protracted build-out of the AGR fleet and the saga of Sizewell B, the UK has never built a nuclear power station on schedule or within budget.

So when Tony Blair’s Labour government decided in 2007 that the UK should once again embark on building a fleet of new nuclear power stations, the omens did not look good. Just a year previously, BNFL had sold reactor vendor Westinghouse to Japan’s Toshiba, while nuclear generator British Energy was under state control having been bailed out in 2004 for £3 billion.

The rationale for the nuclear ‘renaissance’ was straightforward: to provide low-carbon, baseload power as a replacement for aging coal and gas plant, as well as the existing 16 reactors generating 10 GW, all but one of which are officially due offline by 2023. Then as now, however, no new nuclear power plant had been built successfully anywhere in the world without public subsidy.

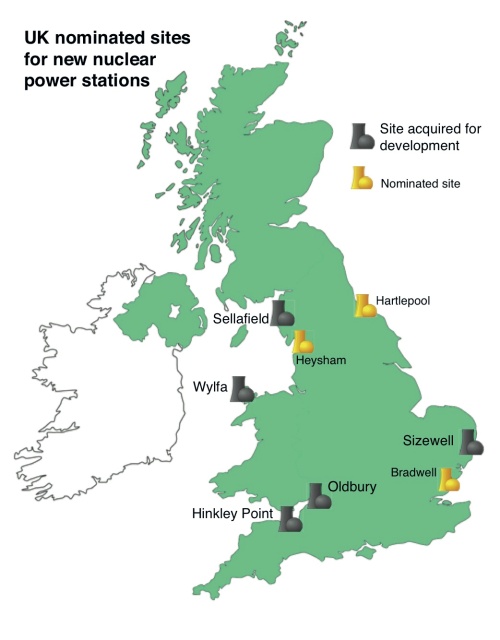

The now defunct Department of Trade and Industry’s May 2007 White Paper, Meeting the Energy Challenge, said the economics of nuclear power had improved; rising fossil fuel prices and carbon pricing had made atomic energy more competitive and a viable private sector proposition. Subsequently, several developers came forward with new build proposals. Approximately 19 GW of new build is either planned or proposed at five UK sites, all in England and Wales1: Hinkley Point C and Sizewell C (EDF Energy); Oldbury and Wylfa B (Horizon Nuclear Power) and Moorside in Cumbria (NuGen).

Big hopes, small steps

Yet these plans have struggled to gain traction. In March, E.ON and RWE put up for sale their joint venture Horizon, which amounts to little more than some land adjacent to existing reactors in Gloucestershire and Anglesey, stating that building nuclear power in the UK would place too much of a burden on their already highly debt-laden balance sheets. Meanwhile NuGen, initially a joint venture between Iberdrola, GDF Suez and SSE before the latter pulled out last September, is not expected to make an investment decision until 2015 at the earliest.

The only nuclear plant being actively developed is Hinkley Point C in Somerset, a 3260 MW, twin-European Pressurized Reactor (EPR) facility. EDF Energy has let £50 million in contracts for site preparation works, although in May it deferred a £1.2 billion civil engineering contract pending a final investment decision (FID) to build two 1.6 GW European pressurized water reactors (EPR).

EDF says it aims to make an FID on Hinkley Point C by the end of the year, but it is still to clear some important EPR licensing hurdles for the HSE’s Generic Design Assessment (GDA). The Office for Nuclear Regulation’s July 5 report stated EDF still had 28 ‘GDA Issues’ to resolve, including security, reactor chemistry and integrity of the inner containment wall, before consent to commence reactor island construction could be granted. It is unlikely these issues will be resolved by the end of 2012.

Need for government support

Yet the most pressing barrier to construction of Hinkley Point C, and any other nuclear plants, is finance. As global head of power at French banking group Societe Generale Allan Baker says, financing nuclear power plants without government support is nigh on impossible.

“No financial institution is willing to take the risk on cash flows over 20-25 years without visible government support for the nuclear industry,” he says. “We have found it incredibly difficult to mobilize capital for an industry which is seen as very expensive and, to be blunt, non-competitive in a competitive electricity market.

“It’s not the costs of nuclear per se, but the uncertainty of costs, which is the killer for financial institutions. If you’re building something which costs $10 billion and there is a 20 per cent cost over-run, then there’s another $2 billion to find. Where does that come from? Does it come from the sponsors or additional debt? And will it be recovered soon, or over the entire lifetime of the plant?”

It is because of this need to offer certainty over construction risks that DECC is offering Feed-in Tariffs (FiT) with Contracts for Difference (CfD) under Electricity Market Reform (EMR) proposals in its 2012 draft Energy Bill. The CfD will offer a fixed price for nuclear output over as yet undetermined period, although it is expected that it will be at least 20 years.

In essence, a CfD is a contract to pay or be paid the difference between a market reference price and a DECC-agreed ‘strike price’. CfDs are controversial, not least because DECC ministers have made repeated statements in the House of Commons that “there will be no subsidy” for nuclear and that nuclear will be on a level playing field with other low-carbon technologies like offshore wind.

In late July DECC entered into negotiations with EDF over the strike price for Hinkley Point C. Indications are that the price will be anywhere between £100-135/MWh. Crucially, £135/MWh is reflective of the current subsidy paid to offshore wind via the Renewables Obligation, while £100/MWh is DECC’s Offshore Wind Cost Reduction Task Force target by 2020 – the earliest that Hinkley Point C could realistically come online.

In a 13 August interview with The Daily Telegraph, EDF Energy CEO Vincent de Rivaz said he expects the strike price for nuclear to be lower than the current cost of offshore wind farms, but declined to say whether it also means matching £100/MWh by 2020.

Running at an estimated capacity factor of 80%, a 20-year CfD for the 3.2 GW Hinkley Point C could, therefore, be worth between £25-40 billion at current wholesale power prices of £45/MWh. This would represent a handsome return on investment for a plant with an estimated construction cost of £7-10 billion.

CfDs are due to come in to effect in 2014 but DECC is taking special measures in the Energy Bill, called ‘Investment Instruments’, to allow EDF to make an FID on Hinkley Point C before the end of the year. The primary instrument is ‘FID Enabling’, which would allow DECC to crystallize the outcome of the strike price negotiations for Hinkley Point C by way of a binding agreement before the Energy Bill gains Royal Assent by the end of 2013.

Hinkley Point B nuclear power station in Somerset. EDF Energy plans to build a 3260 MW, twin EPR reactor Hinkley Point C within the next decade

FID Enabling is ‘nonsense’

FID Enabling, however, is seen by some as deeply flawed. A legal expert told Energy World: “FID Enabling is nonsense. It doesn’t do what it’s intended to do. If you are taking FID before legislation was in place because you were concerned legislation was not in place, you couldn’t take any comfort from anything that was dependent on legislation being passed.

“You don’t have legal certainty. It’s like a ratification provision. It’s sort of says that if the government does something then it will be ratified by being an investment instrument after the event. It is not particularly satisfactory.”

The University of Greenwich’s Professor Steve Thomas says another unknown is whether nuclear CfDs will include price escalators, as they did for CCGTs in the 1990s. “Nuclear suppliers are not going to offer a fixed price contract for the equipment and they are certainly not going to give any guarantees for performance or operating costs. Financiers want to know what happens if things go wrong. This is why there may be escalators in the CfDs.

“This was always going to be the case regardless of Fukushima or even Flamanville and Olkiluoto, which merely confirm that any suggestion of the new generation of nuclear power plants having solved the old problems is, at best, unproven. Whether we would know that would be the case is uncertain. The CfDs of the 1990s were never published. I assume that the companies involved deemed them commercially confidential.”

DECC says that its negotiations with EDF are confidential, although it will publish the agreed strike price in time. However, even if EDF are satisfied with DECC’s offer of support for nuclear, there are two areas where the plan may still fail: European Commission state aid rules and potential judicial reviews from NGOs.

“If I represented Greenpeace I would be wondering what I am going to challenge,” says the legal expert. “I would be thinking about challenging the development consent order and then I would be thinking about challenging EMR.”

In a note on the Energy Bill2, the University of Oxford’s Professor Dieter Helm said that the Energy Bill’s nuclear measures are vulnerable. “The problem with negotiated FiTs, especially for nuclear, is that they are potentially wide open to legal challenge if the strike price is based on questionable forecasts and indeed to the challenge that strike prices include subsidies to nuclear,” he writes.

“Subsidies are being and will be paid, raising the question of how government decides the subsidy level on a case-by-case basis and how “no subsidy” can be defined as “equal subsidy” and what that means given “different subsidies” for each low carbon technology. It is far from clear how the European Commission will treat the implied state aids, or indeed how the government would treat the subsidies issues were there to be a judicial review of the nuclear FiTs.”

Giving evidence to the Energy Select Committee on June 263, DECC’s Director of Energy Strategy & Futures Jonathan Brearley said “the Commission may take different views on different technologies”, but in general DECC believes that the Energy Bill measures, including CfDs, will clear state aid rules.

The counterparty conundrum

Why can they be so sure? Well, one reason is because the Treasury has decided it will not be the counterparty or, in other words, underwriting CfDs. Unfortunately, this decision has put the explicit rationale of EMR – to reduce the cost of decarbonizing the electricity sector – in considerable jeopardy.

Initially, the Treasury was to be the counterparty of CfDs, thus allowing investors to benefit from its AAA-credit rating to reduce the capital costs of investment in low-carbon power generation. Instead, DECC is attempting to fashion an alternative, which would be legally robust while still not technically underwritten by the Treasury.

It remains to be seen whether DECC will be able to offer a satisfactory, state-backed CfD for Hinkley Point C that can clear state aid rules. “Hinkley Point C is looking 50-50 at the moment,” says Professor Thomas.

“We shouldn’t discount the fact the EPR is in a pretty awful state. It will probably take another year to get through the GDA process. I think that Centrica will pull out, which will leave EDF even more exposed. EDF already has a big bill to pay for maintenance of its 58 existing reactors in France. So why would it really want to take a punt in the UK for Hinkley Point C?”

Thomas notes that EDF’s existing fleet of AGRs are set to have their lives extended by an average of five years. This will mean that most AGRs will be running well into the next decade, rather than all 14 being shut down by 2023 as previously assumed.

So if EDF really does pull out of Hinkley Point C, what next? Russia and China are reportedly looking closely at the Horizon sites, but are these realistic plans, or just speculation? Steve Kidd, Deputy Director General of the World Nuclear Association, believes it is highly unlikely Russia would be interested in Horizon.

“The Russians would have to start from scratch to license their reactor and this will take at least four years,” he says. “It’s more of a long-term aspiration. There’s no way that they would buy Horizon and get their own reactor licensed. Whoever buys Horizon has got to use either the EPR or Westinghouse’s AP1000.”

That leaves China, which is building both reactors domestically. Kidd, a regular visitor to China, says: “China is serious, they have lots of money and the State Nuclear Power Technology Corporation (SNTPC) would like to build the AP1000 abroad.

“The UK government would be very happy with more than one reactor design being built. SNPTC tells me that it is extremely keen but it may be biting off more than it can chew, as it plans to build AP1000s all over China. I suspect it’s Westinghouse who is driving this in London, with SNTPC very much in the background.”

Whether or not China is serious, it remains highly questionable whether the Government would, in reality, be comfortable with a Chinese state-owned company owning UK nuclear space. So, if no EDF, no Russians, and no Chinese, then who?

“You can imagine that this will all end up in government hands eventually,” says one utility analyst. “They may nationalise the whole thing.” One potential scenario is for Her Majesty’s Government to take on from EDF the building of nuclear reactors, then selling the power plants after a period of successful power generation, e.g. one year, to the highest bidder.

“Nuclear has got to happen or the lights will go out,” says the analyst. “One way or another, the Government will find a way. But there is a great deal yet to play out before it gets there.”

References:

1. World Nuclear Association Reactor Database: http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf84.html

2. EMR and The Energy Bill: A Critique by Professor Dieter Helm 27 June 2012 http://www.dieterhelm.co.uk/node/1330

3. House of Commons Energy and Climate Change Committee Draft Energy Bill: Pre–legislative Scrutiny – Volume II, 23 July 2012 http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmenergy/275/275ii.pdf

Good article, until the conclusion: ‘ “Nuclear has got to happen or the lights will go out,” says the analyst. ‘

That’s nonsense. Serious investment in renewable energy, in energy-efficient lighting (LEDs) and in education (turn the lights off when you’re not using them), would prevent ‘the lights going out’ as we phase out fossil fuels.

Extrapolate for other, non-light-emitting, appliances.

Posted by Hazel Hedge | October 24, 2012, 3:47 PM